Rest in Power, José Mujica; Dead at 89

His legacy, from a guerrilla fighter to 13 years of harsh imprisonment to the presidency, will loom large in Uruguay

Back in January, I wrote the following substack after news that Jose “Pepe” Mujica’s cancer had returned and that he was forgoing any further treatment. We have just heard news that he lost his battle with the disease. I am reposting my article below for those interested in learning more about his life and legacy. Descansá en paz.

Uruguayan Former President, José "Pepe" Mujica, to Forgo Further Treatment for Cancer

In the United States, January 9, 2025 was marked as a national day of mourning for President Jimmy Carter, whose state funeral was held in Washington DC. The same day in Uruguay was notable for the breaking news that former president (2010-2015), José Mujica’s cancer had returned, spread, and that at 89, he would forgo further treatment.

In the United States, January 9, 2025 was marked as a national day of mourning for President Jimmy Carter, whose state funeral was held in Washington DC. The same day in Uruguay was notable for the breaking news that former president (2010-2015), José Mujica’s cancer had returned, spread, and that at 89, he would forgo further treatment.

The two men’s fates have been tied once before. Jimmy Carter had a profound impact on Uruguay due to his human rights policies during his years as a president, which coincided with some of the worst years of the country’s repressive dictatorship (1973-1985). José “Pepe” Mujica spent that entire period in harsh prison conditions. Carter had actually tried to pressure the Uruguayan military to release political prisoners and improve conditions for those imprisoned. While his policies had some effect in the country, Mujica was not a beneficiary.

Mujica had joined the Movimiento de Liberación Nacional-Tupamaros (MLN-Tupamaros)—a Marxist-Leninist urban guerrilla group—in the mid-1960s. The group was inspired by the Cuban Revolution, and was met with force by an increasingly repressive Uruguayan government with the backing of various US administrations that sought to counter the group at all costs. Mujica was captured on four different occasions, twice escaping from Punta Carretas prison in truly spectacular fashion. He was caught for the final time, however, in 1972 and that time he would not leave the military’s custody for more than thirteen years.

He suffered the years of the dictatorship in appalling conditions. Most of his time was spent in solitary confinement, with more than two years being held at the bottom of a well. The torture he experienced was aimed specifically at breaking him mentally and physically. He was not released until March 1985, as one of the very last political prisoners in Uruguay that the military let go only as part of the final stages of its exit from power.

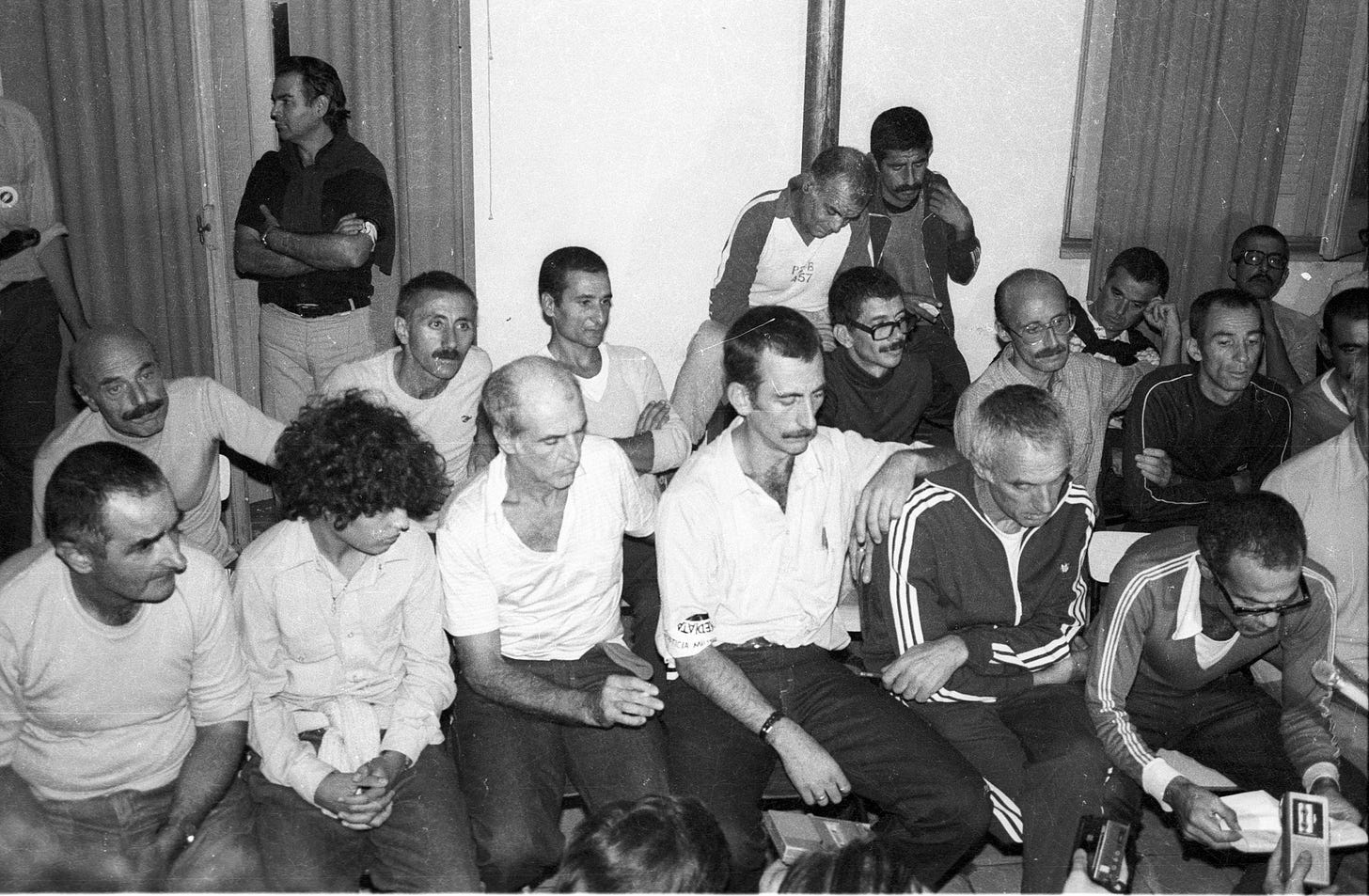

Photo Credit: CDF. Mujica is on the far left in the front row on the day of his release

In the years that followed the military’s rule, he played a central role in the Tupamaros moving to legitimate political spaces as part of the Frente Amplio left-wing coalition. In 1994, he was elected to the lower house of Parliament, and in 1999, he was elected as a senator in the upper house. When the Frente Amplio’s Tabaré Vázquez won the presidency for the party’s first time in the country’s history in 2005, Mujica served as his Minister of Livestock, Agriculture and Fisheries. However, presidents in Uruguay cannot serve consecutive terms, and Mujica ran in 2009 to replace Vázquez—which he successfully did.

His presidency was part of the pink tide, or leftward turn, in Latin America in the early 2000s, but Mujica distinguished himself even among his contemporaries during this period. He passed a slew of progressive policies, the perhaps most well-known ones being same-sex marriage, legalizing the sale and distribution of marijuana to counter the illegal drug market, and legalizing abortion. His lifestyle also attracted international attention and admiration, with the international press giving him the title of the “world’s poorest president.” He refused to live in the presidential palace and instead continued to reside in a small farmhouse on the edge of the capital. He gave away most of his presidential salary to charity and drove a 1987 VW Beetle.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia

25.01.2023 - Presidente da República, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, durante Encontro com o ex-presidente da República Oriental do Uruguai, José Mujica, e com Lucía Topolasnky. Montevidéu - Uruguai. Foto: Ricardo Stuckert/PR

He also famously never wore ties even at in the most prestigious halls of power such as the United Nations or when meeting with the President Barack Obama at the White House.

Photo Credit: Wikimedia

Other times, he even eschewed closed toed shoes. When other ministers wore full suits and ties, he would show up without a jacket, tie, and wearing sandals.

All these aspects only added to his global mystique, which was furthered in popular culture. Netflix produced a documentary about his life, El Pepe: A Supreme Life. His imprisonment was also dramatized in A Twelve Year Night, a film about his, Mauricio Rosencof, and Eleuterio Fernández Huidobro’s horrific experiences. Carolina de Robertis wrote a fictionalized account of Mujica’s prison life in The President and the Frog.

I lived in Uruguay during parts of his presidency, coming down for research during the U.S. summer of 2012 and then the entire year of 2014. While popular domestically, he never had quite the same mystique in Uruguay that he did with international audiences. At home, he was subject to day to day governing pressures. Among other critiques, some within the human rights community found fault with the backseat that accountability initiatives took during his time in office. Despite suffering incredible abuses during the dictatorship, some believe that he felt centering justice policies for the military abuses would open himself up to attack for his actions as a Tupamaro and distract from his broad, progressive governing priorities. Thus his political will to demand justice was never a centerpiece of his presidency.

Yet, in 2014, I went to Uruguay’s Marcha del Silencio—an annual march held on May 20 every year to demand justice, truth, and accountability for the victims of the country’s state terrorism. May is almost winter in Uruguay and I remember distinctly the frigid weather and light rainfall that accompanied the march down the Avenida 18 de Julio. Amazingly though, halfway through the walk, I turned around to a slight commotion where I saw President Mujica join the march with his wife Lucía Topolansky.

photo by Debbie Sharnak

Without almost any security, he inauspiciously joined the march, and at the end, quietly exited with the rest of the protesters.

It was one of the more incredible experiences of my research year, although the implications of his presence on his personal and political views of accountability remain largely unknown. Unable to run for a consecutive term, he exited the presidency a year later and returned to the Senate where he served until resigning as his health began to deteriorate in 2020.

Mujica declared today that he gave his last interview to the Uruguayan paper, Búsqueda. He revealed that the cancer has returned and spread. “I am dying,” he said. “I am old and have two chronic illnesses." He explained that he couldn’t undergo further treatment because his body would not be able to handle it.

An outpouring of support followed the announcement. Some came from Yamandú Orsi, Mujica’s political mentee that was just elected in November 2024 to return the Frente Amplio to power in March of this year. Others came from far and wide, including the art below from Uruguay Noma (the amazing artist who did the cover art for my book) and wrote the caption “Fuerza Pepe” underneath. There is no doubt that Mujica’s long and storied career—from guerrilla to political prisoner to the presidency—will have an enduring impact in both Uruguay and around the world in a way that few other Uruguayans have done.