The "unofficial" coup in Uruguay: the Boiso Lanza Pact

Unsettling official start dates to dictatorship

It’s been a few months (thanks tripledemic) but I am back today to explore the Boiso Lanza Pact, which President Juan María Bordaberry and military commanders signed on February 13, 1973. The pact enabled the Uruguayan armed forces to assume virtual control over the Uruguayan government, even though the autogolpe did not officially occur until more than four months later on June 27, 1973.

So, let’s take a step back. First, what was going on in Uruguay at this point? By early 1973, the country had been waging a war against the Left for five years. The Tupamaros, the urban guerrilla group, had been virtually defeated the year before by the police and armed forces. Many Tupamaros members were either in prison or killed, and those remaining free had largely disbanded as a result of its depleted leadership. Yet, the military was intent on increasing its power and control of the country against the political and social left. Events in February 1973 offered a key opportunity for the armed forces to increase its position within the country, one that I would argue proved irreversible.

It all began on February 8, 1973. That day, Bordaberry appointed retired General Antonio Francese to be the Minister of Defense, a move the chiefs of the armed forces deeply opposed. Francese was an avowed constitutionalist and outspoken in his commitment to keep the armed forces within constitutional boundaries, which meant subordinate to the civilian government. Only the Navy was in favor of his nomination. The chiefs of the other branches demanded that Bordaberry withdraw the nomination, which he refused to do. In fact, at 10:30pm that night, Bordaberry went on Canal 4 to call on citizens to support his nomination and gather in Montevideo’s central square, Plaza Independencia, to demonstrate their solidarity with his choice. Only two hundred people arrived, indicating Bordaberry’s political isolation and weakened position within the country.

The situation escalated quickly. The next morning, on February 9, 1973, the Navy barricaded the entrance to the Ciudad Vieja. Not to be outdone, the military drove its tanks into the streets and occupied radio stations where they called on the Navy to join the rest of the military branches to oppose Bordaberry. They quickly released communiques, proposing its political agenda to the country. Decrees no. 4 and 7, most importantly, suggested a nationalist-based agenda focused on encouraging exports, eliminating foreign debt, attacking corruption, reorganizing the public administration and tax system, eliminating any terrorist threats, among other measures. Within two days, the Navy’s commander Vice Admiral Juan José Zarrilla resigned, and Captain Conrad Olazaba joined the other forces to push for a military takeover of the government on its communiques’ principles.

Former Colorado party representative Fernando Amado has in fact called this the “technical” coup d’état. In its aftermath, the military and Bordaberry met at the Boiso Lanza military base in Montevideo to hash out an agreement that allowed Bordaberry to remain as official head of the country, while all functional power had been transferred to the military.

(Foto: Bordaberry at the Boiso Lanza Air Force base with commanders)

Indeed, Bordaberry accepted all the military’s demands. The Pact created a National Security Council [Conejo de Seguridad Nacional (COSENA)] which had control over the civilian government. COSENA included commanders of the three armed services as well as the ministers of defense, interior, foreign affairs, and the economy. The armed forces would have complete authority in the nomination of the ministers of defense and interior, ensuring their dominant role over Bordaberry and his subordination to figurehead. In essence, the military had complete veto power now over the government’s functioning. The change fundamentally altered the relationship between the armed forces and the civilian government, which until 1973, had officially remained outside formal politics.

One argument in Of Light and Struggle is that Uruguay’s decline into dictatorship and difficult transitional period back to democratic rule challenges easy categorizations of dictatorship and democracy. As opposed to Chile’s dramatic coup in September 1973, there was no such obvious moment that one can trace to the exact date a dictatorship was installed in Uruguay. Many look to Congress’s closure as the beginning of the auto-golpe in June 1973. However, the Uruguayan people had experienced years of the government’s draconian methods in supposed battle against communism, and the unofficial takeover in February at the very least points to months before June as a critical juncture point in the military’s increasing power within government. The Bioso Lanza pact is but a footnote in many histories of Uruguay’s military rule. Yet, I would argue, centering its importance demonstrates the gradual and slow decline of the country’s democratic institutions and offer watchers of democratic backsliding an example of how power can shift between elected representatives and more authoritarian forces.

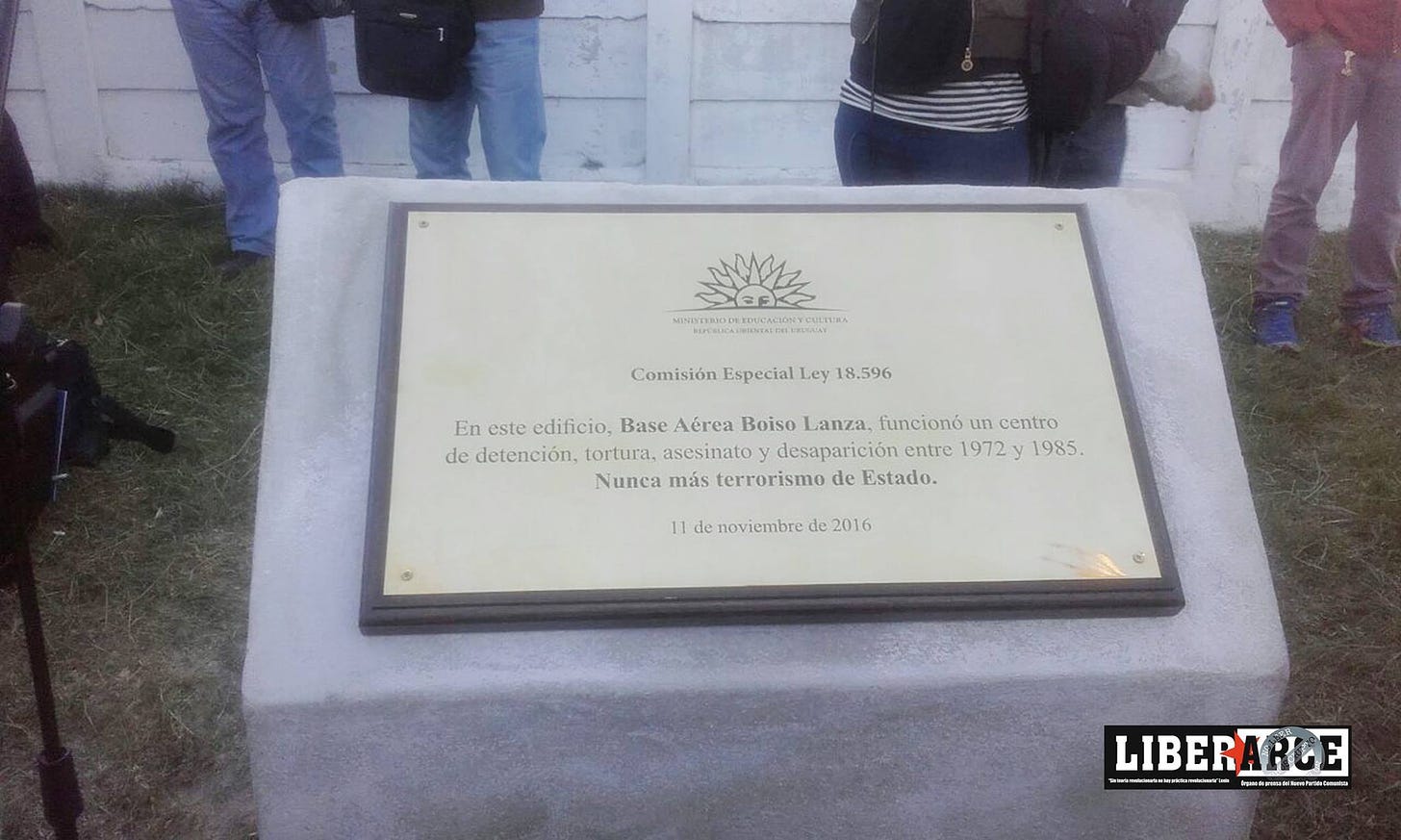

The Boiso Lanza Base also should be remembered for another reason. The Cap. Juan Manuel Boiso Lanza Air Base is part of the collection of historic air force bases within the country, and this one in particular is partly remembered as the ‘birthplace’ of the country’s Air Force. Yet, during the dictatorship, it was also a detention and torture center. Starting in 1972, even before the Pact was signed, those activities took place on site. Overall, more than 100 people are believed to have been detained on the base during the dictatorship. Only in 2016, though, did the State place a placa de memoria on the air force base, thus acknowledging not just the historic Pact that occurred there, but the human rights violations as well. The Pact may have been signed fifty years ago, but its relevance as a site of memory and justice continues today.

(Foto: Federico Gutiérrez)

(Foto: Periódico LiberArce)

Last but not least for this newsletter, I wanted to point a link to Penn Press’s Spring catalog, which so wonderfully features @uy_noma’s beautiful artwork.

The book can be pre-ordered here for anyone interested!